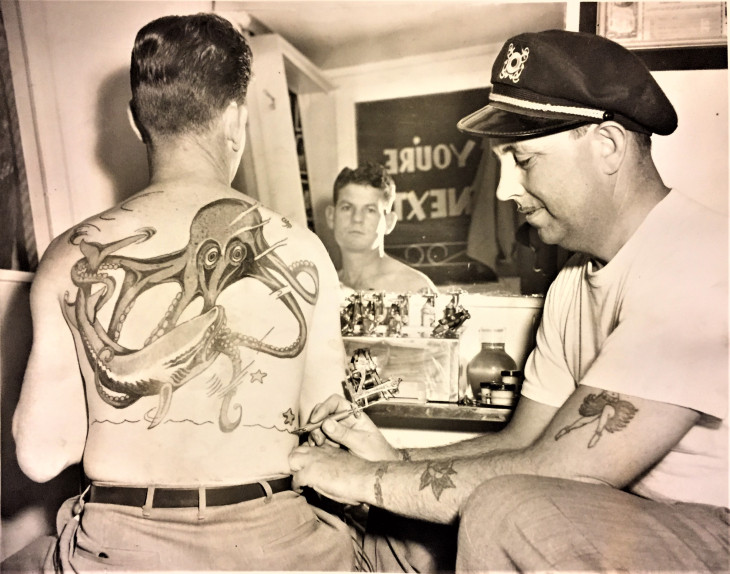

The Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum has scheduled a Jan. 4-Feb. 29 exhibit highlighting California’s history of women with tattoos, and a cultural transition that has resulted in more skin art on women than on men. Times definitely have changed since the 1950s, when Vallejo’s own George “Old Doc” Webb inked thousands of sailors in his Lower Georgia Street parlor. Despite his old-school roots, Webb saw the transition coming and praised the women who helped to make it happen.

Local tattoo artist Jeani Day Kyair, one of the scheduled speakers during the museum’s “Tattooed and Tenacious: Inked Women in California’s History” exhibit, notes that Webb took on “Apache Jil” Tong as an apprentice in his San Diego tattoo parlor, opened after his 10-year run in Vallejo ended in 1959. Tong, who now has a tattoo business in Reno, in turn trained Kyair, who has been in business in Vallejo for 25 years.

“Doc Webb was pretty no-nonsense. He didn’t suffer a fool,” Kyair says. “He didn’t make it easy for women who were apprentices. Women had to work twice as hard. We definitely had to earn our place. I think he would have mixed feelings about the way things have turned out today. Like any of the old-timers, he would have felt times were better back then.” But Webb also gave credit to talented women artists, describing them in his 1978 book, “The Honest Skin Game,” as an important part of the tattoo world and “a fine uplift to the art.”

Webb, who died in 1986, remains one of America’s best- known tattooers, according to tattoo artist “Doc” Don Lucas, a Vallejo native. Lucas, now living in Louisiana, has a huge collection of sheets of “flash” — designs Webb created — along with some of the many artifacts displayed and novelties sold in his shops. In his 230A Georgia St. location, you could find everything from wood carvings to magic tricks, exploding cigarettes, fake dog poop, skull rings and whoopee cushions. He even had a pet monkey, “Bobo,” and a small hand-cranked organ. Webb, who tattooed in the states of Washington, Alaska and California, bought his first supplies in 1926 and started out in Seattle. He left Vallejo due to the city’s massive redevelopment project that resulted in demolition of the entire Lower Georgia Street district. Webb relocated in San Diego’s old Gaslamp district, where he worked for another 20-plus years.

In a 1977 interview, Webb talked about the then-developing changes in what had been a business whose customers were mainly men. “Girls in their 20s will come in and tell me their mothers would have a fit if they knew they were getting tattooed,” he said. “Then the mother finds out and comes in because she wants her own tattoo.” Webb added that by the mid-1970s, women made up a quarter of his clientele, and the percentage was growing all the time.

Today, curator Amy Cohen, who put together the ”Tattooed and Tenacious” exhibit that premiered in 2015 at the Hayward Area Historical Society, says almost a quarter of American women have permanent ink, compared with 19 percent of men. Younger people are more likely to be tattooed: more than a third of Americans between the ages of 18 and 40 have skin art.

The Vallejo museum exhibit, being circulated by San Francisco-based Exhibit Envoy, includes a section on “Native Ink,” which focuses on women in tribes such as the Pomo, Miwok and Hupa who practiced body tattooing. Almost every California tribe had a tattooing tradition. Besides tribal members, captives also could be tattooed. That included a young girl, Olive Oatman, who was kidnapped while traveling west with her family in 1851. She returned to white society in 1856, tattooed on her chin and arms.

Also part of the exhibit is a section dealing with wealthy women and tattoo fads. They included Aimee Crocker, the Sacramento railroad heiress who got many tattoos throughout her unconventional, world-traveling life. Another panel says Crocker and other “elite” California women may have been inspired by Lady Randolph Churchill, mother of Winston Churchill, who sported a snake tattoo on her wrist. Also displayed are heavily inked “tattooed ladies,” mainly working-class women who were covered with permanent body art from neck to feet and made good money as circus sideshow performers starting in the 1880s.

By the early 1900s, advances in tattoo technology resulted in intricate designs. One “tattooed lady,” Lady Viola, had the faces of six presidents on her chest and an image of the U.S. Capitol on her back. Another, Artoria Gibbons, had Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece “The Last Supper” tattooed across her back. Betty Broadbent, one of the most famous “tattooed ladies,” had more than 350 distinct designs, including images of Charles Lindbergh and Queen Victoria. Challenging conventional standards of beauty, she displayed her tattoos during a televised beauty pageant at the 1939 World’s Fair — but didn’t win.

The reputation of tattoos suffered after World War II with the rise of inked-up outlaw bikers, gang members and felons, and that taint spread to women with tattoos. But the countercultural revolution of the 1960s brought about a renewed interest. When Janis Joplin performed, women noticed her body art and wanted their own. The feminist movement of the 1970s, with its message of women reclaiming their bodies, brought further acceptance and tattoos now are more popular than ever. Tattoos may be permanent but can the same be said for the current popularity trend? “There’s no way to know for sure,” exhibit materials state. “But one thing is clear: the future of tattoos will continue to be shaped by its past, and by the tenacious, inked women who staked out their place in California history.”

— Vallejo and other Solano County communities are treasure troves of early-day California history. The “Solano Chronicles” column, running every other Sunday in the Times-Herald and on my Facebook page, highlights various aspects of that history. Source references are available upon request. If you have local stories or photos to share, email me at genoans@hotmail.com. You can also send any material care of the Times-Herald, 420 Virginia St.; or the Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum, 734 Marin St., Vallejo.